Carlos Grande

WARC Online

Of the many trends which have arisen to challenge existing models of brand communications, online social media is one of the most important.

By publishing the report, "Social Media Futures - The future of advertising and agencies in a networked society", written by the Future Foundation, the UK-based Institute of Practitioners in Advertising (IPA) has joined a debate on two central questions about the phenomenon:

- Does social media require a new model for brand communications?

- If so, how can agencies put this into practice?

What follows is a summary of some of the report's findings and of a related public discussion, hosted by the IPA, together with some recent WARC Online articles in this area.

The full Social Media Futures report is available for purchase from the IPA.

Introduction

Social media's impact has been fast, sizeable and international, as indicated by a recent report

UK social networkers also tend to visit the same handful of websites. When Ofcom, the UK media regulator, asked respondents which of their online profiles they updated most often, 49% said Facebook, followed by 21% MySpace and 19% Bebo. Other sites barely registered. This consolidated pattern - with variations for strong local players such as Orkut in Brazil - is increasingly being found in other markets.

The peculiarly participatory and user-centric nature of social media sites has been well documented. Furthermore, there is evidence, albeit ambiguous, that as part of overall growth in online usage - itself driven by social networking's surge - some consumers report spending less time with some established media (especially print), a trend reported by research from the European Interactive Advertising Association.

The upshot of all these combined factors is that social networking sites have the potential to become large-scale, interactive branding channels at a time when consumers' media habits are changing. But examples of successful social media marketing have been strikingly absent in both number and quality.

The IPA/FF report quotes one estimate that Facebook will earn about $5 per user per year in 2009 advertising revenue. This is a poor return for the estimated 3,000 minutes per year the average Facebooker will spend on the site. Although McDonald's, Sony, Dove, Channel 4, Intel and Aquafresh have all been among those advertisers which have bucked the trend, there have been many high profile instances of social media initiatives which flopped.

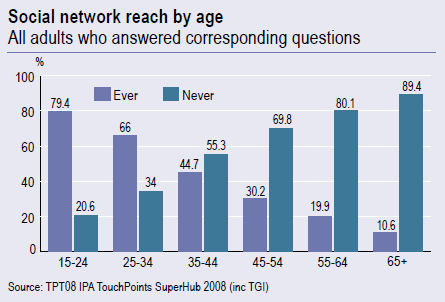

The problem is not a shortage of available formats, which the report groups into five broad categories: from the UK communications regulator, Ofcom. In the UK, for example, networking websites have achieved significant reach among both genders - and not just among 15-24 year olds.

- Interruption: display ads, pre-roll video, tagging, email

- Engagement: viral film, online programming, affiliate marketing, competitions, promotions, word of mouth

- Participation: brand blogs, community sites, branded environments, bulletin boards, online surveys

- Facilitation: branded applications, third party blogs, widgets, fan campaigns

- Conversation: brand conversations; brand defence.

But the common theme among these formats is that audiences cannot be planned, bought or measured for such campaigns as they could by using mainstream media formats. This means that even if the medium's promise is that of a high-impact, low-cost channel, the danger is it will prove high-waste and low-impact.

The report's authors have therefore attempted to précis current theories on how influence and content permeates online social networks, and to suggest basic principles for the media and creative strategies best suited to the genre.

At the outset they quote the analogy, used by blogger David Armano, for the way content or information spreads among people. Armano compares this to a series of serial ripples in a pool which are formed each time content is distributed. These can be classified according to levels of influence:

- Level 1: mainstream media

- Level 2: open networks such as blogs, feeds, websites etc

- Level 3: closed networks such as Facebook, MySpace

- Level 4: distribution via individuals and email lists.

In this scheme, all ripples are potentially valuable since mainstream "ripples" can be fewer and broader in reach, but smaller ripples can be more frequent, lower cost and more targeted.

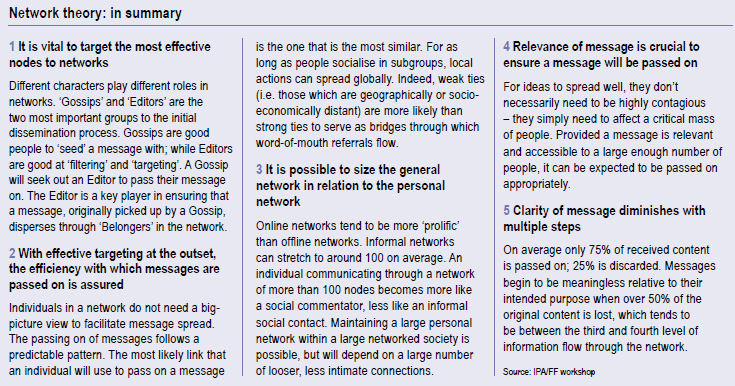

Using a trawl of academic studies, the report identifies five areas as most relevant to understanding the way communications work in online social networks.

1. Targeting

Unsurprisingly, much academic research has argued that social networkers' behaviour is closely correlated to the degree to which they are at the centre or the periphery of a group of connected users. This has underpinned the belief that social networks contain key influencers who "sit between the most other people or who are directly connected to the most people". Such influencers can be categorized by the general roles they perform.

Other studies have identified different numbers of social media types; the IPA/FF study describes three built around a trio of core characteristics:

- Gossips: the expansiveness of a user and how many other individuals a user habitually communicates with.

- Editors: a user's propensity to filter and target the messages he or she receives and send these on.

- Belongers: - the willingness of a user who receives a message to pass this message on to a third party.

Academic researchers have argued that "Gossips" are disproportionately likely to be the original sources of a message and are therefore "good people to seed a message with". Conversely, "Editors" are popular recipients of a message, originated elsewhere, because, by filtering and targeting, they ensure the efficient dispersal of a message across the network. "Belongers" are defined by their willingness to join the group in question, thereby increasing the "networked" reach of conversations.

The authors write "it is clear that the choice of key players for dispersing a message through a network depends on more than the individual characteristics of each person; the optimum combination must be sought".

It should be said that a previous Ofcom report categorises these segments differently, such as "Alpha Socialisers" and "Attention Seekers", and also attributes broad demographic characteristics to them.

2. How messages travel

Users on social media websites are not aware that they are forming networks in this way and may even by opposed to the idea to be seen as any kind of conduit. Nevertheless, some common-sense principles seem to shape interactions across the network.

For instance, a user who receives a message via one particular link (for instance, from a work colleague) is most likely to forward it via a similar link (namely to another work colleague).

Like attracts like, with users of similar age, language and location communicating more often with each other than with members of different sub-groups. But referrals can also jump between groups which appear only weakly related.

3. Small world

Informal, online networks tend to range in size up to 100 individual contacts (sometimes described as nodes) since "an individual communicating through a network of more than 100 nodes becomes more like a social commentator, less like an informal social contact".

This is still a larger number of contacts than the nearest equivalent network in the offline world would typically hold. However "Friend-ing fatigue" is a common complaint, and it is likely that the longer social networkers use a site, the greater their propensity to maintain active links with a more manageable number of contacts, whilst culling others.

Social networkers also tend to see their contacts as layers - stretching from the global, through layers of greater intimacy and knowledge, towards core clusters of established contacts and peers with whom communication is regular and informal.

In an echo of the "six degrees of separation" theory, the report also cites a 2008 analysis of a month's worth of anonymous data sent across Microsoft's instant messenger system (totaling some 30bn conversations) which found that the average path length of messages was indeed about 6.6 users.

4. Messaging priorities

In this context, two main variables tend to show how efficiently and accurately messages flow across the network.

- Relevance: ideas do not need to be contagious, but they do need to affect a critical mass of the audience.

- Clarity: clarity of the initial message diminishes with each progressive step it travels, turning communications into a type of Chinese Whispers.

5. Theory into Practice

By applying greater understanding of consumers' behaviour in networks, it should, theoretically, be possible to create communications which have a high impact on targets, with little wastage and at relatively low cost. Although views vary on this, it should also be possible to treat social media as another channel alongside traditional media, albeit one with a distinct character.

Some studies suggest that analysis of networkers' behaviour can also provide indications as to their brand preferences, or their more general receptiveness to a particular brand's messaging. The authors quote academic research which found that "Consumers with joint membership in a [brand] subgroup…for one good, are more likely to prefer the same brand for other goods than are those consumers who belong to a different or to sub-group".

Media planners have several other factors to consider. First, to be dispersed globally, messages must first be passed on locally within small-subgroups and networks. Relevance to an appropriate set of targets is therefore key. However, brands must also be prepared in the event that a message, originating locally with a small sub-group, widens out into a much broader audience reach.

For planning purposes, it is important to remember too that an individual contact who likes to chatter will chatter first to individuals directly connected to him or her. Finding the right place to seed messages is therefore vital. And since it is difficult to find the optimum number of key players for a message to reach, it is more important to choose the number of individuals to seed with, rather than the most influential individual/community with which to seed material.

Creatively, the use of pictorially rather than text-led campaigns leaves brands less vulnerable to distortion via the "Chinese Whispers" effect. The use of a sequential or piecemeal message is also high-risk, since there is no guarantee that all the necessary messages in a series will be relayed to sufficient users.

The report summarises these details into the following planning rules:

Discussing the findings

A discussion on the report's themes featured contributions from John Wilshire, Head of Innovation, PHD Media; Charles Wells, MD of Kinship Networking; Cheryl Calverley, Marketing Manager, Unilever; Nigel Gwilliam, Communities Senior Manager, IPA.

Points that emerged from the discussion included:

- Social media can be deployed using many of the same agency skills as are applied in traditional media such as the creation of compelling content to increase "talkability".

- However, measurement of social media impact remains difficult; observation, comparison and experimentation are likely to be the order of the day for some time.

- Regulations applied to traditional media advertising will increasingly be applied to online social media.

- Social media may change the way advertisers pay for branded content; it may also lead to roles such as monitoring and management of online chatter being done in-house or by PR-led agencies.

- The internet and technology generally brings the threat that agencies will be disintermediated by technologists (the archetypal "12 year-olds in a garage"), but agencies' skill in managing client relationships will still count.

- The majority of chatter about brands may originate outside brand-owners in future.

- Brands should take an inclusive and humble approach to brand chatter rather than "wade in and chat". They should remember that a brand's "relationship with a consumer is so much less important to that consumer than the relationship to help speed that change".

Related articles on WARC Online:

- Forum - How does Web 2.0 stretch traditional influencing patterns?

- Social media explained

- Should you advertise on social networking websites?

- The Relationship between Consumer Social Networks and Word-of-Mouth Effectivenes

Related case studies

- Aquafresh - Iso-Active launch

- Caterer.com - Little Gordon

- Making the BRAVIA brand famous through effective social network media

- Cadbury - Wispa re-launch

| Carlos Grande is editor of WARC Online. He can be contacted at carlos.grande@warc.com. He joined WARC in 2008 after eight years at the Financial Times, where he was latterly marketing correspondent. Previously, he was acting deputy on the FT's UK companies newsdesk and a senior UK companies reporter. |

No comments:

Post a Comment