Thanks Trevor @ Boxes and Arrows for this insightful post on approaches to IA

by Trevor van Gorp on 2008/08/07 | [9 Comments]

We create software and websites to display and represent information to people. That information could be anything; a company’s product list, pictures of your vacation, or an instant message from a friend. At this moment, there’s more information available to you than at any other time in history.

All this information has a lot of positive effects, but it also creates challenges. “What information consumes is rather obvious; it consumes the attention of its recipients … a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention” (Simon 1971). When attention becomes a scarce resource, it’s important to invest it wisely. Information architects and designers play a critical role in ensuring the products they design provide users’ with a return on their investment of attention.

The psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1990) has described focused attention as “psychic energy”. Like energy in the traditional sense, no work can be done without it, and through work that energy is consumed. Most of us have experienced a mental/emotional state where all of our attention (or energy) is totally focused on an activity. Csikszentmihalyi (1990) named this state “flow,” based on how participants in his studies described the experience.

In this state of consciousness, people often experience intense concentration and feelings of enjoyment, coupled with peak performance. Hours pass by in what seems like minutes. We tend to enter these states in environments with few interruptions, where our attention becomes focused by a challenge that we’re confident we can handle with our existing skills. Feedback is instantaneous, so we can always judge how close we are to accomplishing our task and reaching our goal. The importance of the task influences our level of motivation and perceptions of how difficult the task will be.

Attention and Flow

The elements associated with the flow state can be classified into the three areas; 1. Causes of Flow 2. Characteristics of Flow 3. Consequences of Flow (Novak, Hoffman and Yung, 1999).

1. Causes of Flow

- A clear goal

- Immediate feedback on the success of attempts to reach that goal

- A challenge you’re confident you have the skills to handle

2. Characteristics of Flow

- Total concentration and focused attention

- A sense of control over interactions

- Openness to new things

- Increased exploratory behavior

- Increased learning

- Positive feelings

3. Consequences of Flow

- Loss of consciousness of self

- Distortions in the perception of time

- Activity is perceived as intrinsically rewarding

As designers, we focus on the elements that precede or cause flow. Users visit sites with pre-existing goals (e.g., finding information about a product). These goals evolve over time as users complete tasks and their attention is drawn to other information. The main elements designers can control are:

- Providing immediate feedback

- Balancing the perception of challenge against users’ skills

Designing for Flow

You don’t need to take a course or learn a new software package to design for flow. In fact, you’re probably already doing it. Begin by considering the desired outcome of every interaction and then removing everything that distracts the user from accomplishing that outcome.

Start by removing distractions or impediments wherever possible. For both physical and interactive products, this means reducing or eliminating both external (i.e., environmental) and internal (i.e., pain, discomfort, anxiety) distractions that cause emotional responses like frustration or physical discomfort. Emotions demand and divert the user’s attention. Providing immediate feedback for all user actions helps to reduce user anxiety. The effective use of layout, information design, typography, interaction design and information architecture all help in balancing the perception of challenge against the user’s skill level. Information should be broken down into manageable “chunks” that don’t overwhelm users cognitive faculties.

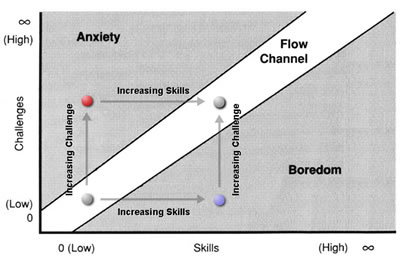

When it comes to balancing the users’ perception of challenge, think of it this way: too much challenge with too little skill causes anxiety; and too little challenge with too much skill causes boredom.

Flow occurs at the boundary between boredom and anxiety. Think of it as a channel that runs between anxiety and boredom.(Figure 1)

Figure 1: Anxiety, Boredom and Flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990)

(captions added van Gorp, 2006)

As the challenges we face increase, we become more anxious and lose flow. Re-entering flow involves increasing our skills to match these challenges and reduce anxiety. As we increase our skill level, we become bored unless we increase the challenge to match our greater abilities.

To understand how we can reduce distractions, let’s examine the different elements of flow again to see how each can be applied to user experience. The causes of flow have the most implications for website and application design.

Causes of Flow

1. A clear goal…

The user navigates to accomplish a task, like seeking information on a particular topic or surfing for fun. This is an evolving goal, dependent on the options presented to the user and aided by logical information architecture, intuitive navigation, effective wayfinding and clear options for proceeding like information scent, breadcrumbs, meaningful labels, clear page titles, etc.

2. With immediate feedback on the success of attempts to reach that goal…

The user receives quick, sensory feedback in the form of a visual shift and/or sound from links, buttons, menus, or other navigation items.

3. Presented as a challenge that you have the skills to handle.

The opportunities for action are balanced with the user’s ability. At a basic level, this is accomplished by providing an uncluttered interface and eliminating unnecessary information to limit the user’s cognitive load. As the users’ skill increases over time, the interface can increase its complexity as well. Adaptive interface technologies allow the user to adjust the complexity of the interface to meet their enhanced skills.

Flow and Emotion

Flow tends to occur in situations with higher levels of challenge and skill. If the challenge is too easy, or user skill levels are very high, anxiety can be so low that there is little motivation to do anything. This level of activation or “arousal” in the body is the physiological (i.e., bodily) dimension of emotion. The level of arousal affects how intensely we experience a given emotion, and intense emotions demand our attention. In evolutionary terms, it’s easy to see why; the more attention your ancestors paid to predators, the more likely they were to survive and reproduce, passing their genes on to their descendants, people like you and me.

Both pleasant and unpleasant objects and experiences can increase arousal levels. Frustration and the excitement both increase arousal levels. So do large images, bright colors, and high contrast (van Gorp, 2006). For example, increasing the size of an image and moving anyone in it closer within the frame increase arousal levels.

Figure 2: Interpersonal Distance and Arousal

How does looking at the picture on the right make you feel compared to the one on the left?

The key to balancing arousal is to match the perceived challenge to the users’ skill level. Since skill levels differ from one user to the next based on their previous experiences and the type of task, interfaces should be very user-friendly but also allow more advanced users to find challenges appropriate for their skill level. These challenges can include the visual aspects as well as the content (King 2003). To put it simply, everything about a site, including content, information architecture, interaction design, and visual design can contribute to flow.

Goal-directed vs. Experiential Use

Different motivations for using a website require different designs to facilitate flow (Novak, Hoffman and Yung 1996). Novice users tend to see the Internet in a playful way, while more experienced users tend to view the Internet in a more utilitarian way (King 2003). This leads to a distinction between experiential and goal-directed use. Flow tends to occur more often during goal-directed use, because of the higher challenge involved.

Novice Users – Experiential use

- Less challenging

- More exploratory

- Entertainment-oriented

Experienced Users – tendency towards Goal-directed use

- More challenging

- Less exploratory

- Connected with tasks (e.g. research, work and shopping)

The lower level of challenge in an entertainment-oriented, experiential site means there is a lower level of anxiety connected with its use. Someone who is less anxious is more capable of using creative thought to determine how to navigate a website and overlook minor problems. Motivation here is driven by subconscious arousal triggered by interesting visual elements, bright colors or high contrast. Experiential sites can and should be more arousing visually to demand the greater attention that can lead to flow experiences.

Figure 3: Disturbia film site

An example of a visually rich, entertainment-oriented site with little or no challenge involved.

The greater challenge of completing tasks (possibly under deadlines) on a goal-directed site creates more higher arousal. Anxiety makes users less able to think creatively when problems are encountered. If a product will be used in a stressful environment, like a hospital operating room, usability becomes crucial. All relevant information needs to be close at hand and visible and feedback should be clear and immediate. A goal-directed site can and should be less visually rich so that users, already anxious at the prospect of a challenging task, are not overwhelmed.

Figure 4: Yahoo

When tasks are particularly unpleasant, we often lack the motivation necessary to complete them. In these cases, increasing the arousal level through the use of narrative can increase the user’s motivation. The Tango Tax website uses visual elements that resemble those found in movie posters and has a high contrast, cinematic feel that increases arousal. The software also introduces the classic cinematic narrative element of “us vs. them” to help increase user motivation.

Figure 5: Tango Tax website

Conclusions – Traits of Websites that Encourage Flow

How you apply these ideas depends on your target audience, as well as their internal and external use contexts. Consider the likely emotional state of your users. Are there loud noises, crowds, brightly colored objects or other distractions in the user’s environment?

Here are some basic website traits that will help to encourage flow.

- Clear navigation: Make it easy for the user to know where they are, where they can go, and where they’ve been, by including signposts such as breadcrumbs, effective page titles, and visited link indicators.

- Immediate Feedback: Make sure all navigation, such as links, buttons, and menus provide quick and effective feedback. Offer feedback for all user actions. When this isn’t possible, provide an indicator to hold the user’s attention while waiting (e.g., progress bar).

- Balance the Perception of Challenge With the User’s Skill: Since user skill levels differ, it’s up to you to balance the complexity of the visual design with the number of tasks and features people can use. Consider whether they are likely surfing experientially for fun or completing an important task. Tailor your sites to your audience’s scenario of use: more visually rich for experiential use and less so for goal-directed use.

Adaptable interfaces that allow the user to increase or decrease the perceived challenge by choosing how much detail is displayed. Simplicity helps reduce anxiety for both novices and experts, which is especially crucial in highly stressful situations. Options for information-rich displays can introduce challenge for more experienced users.

Whether you’re an information architect, interaction designer or visual designer, your work should compel users to invest their attention, and then provide them with a return on that investment.Remember, designing for flow doesn’t require a new set of tools or skills – only a different way of thinking. Finding the right balance of design and challenge can help focus attention and create flow, which results in immersive and engaging user experiences.

References

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. (1990). Flow – the Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper Perennial.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1977). Beyond Boredom and Anxiety, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Copyrights: Journal of E-Business (International Academy of E-Business). All rights reserved. Journal of E-Business, Vol. 1, Issue 2, December 2001.

King, Andrew B. “Chapter 2 – Flow in Web Design.” 2003. http://www.websiteoptimization.com/speed/2/ accessed on January 21/2007.

Fogg, B.J. (2003). Persuasive Technology – Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers.

Hoffman, D.L, Novak, T (1996), “Marketing in hypermedia computer-mediated environments: conceptual foundations’”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 60 pp. 50-68.

Norman, Donald A. (2004). Emotional Design – Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things. New York: Basic Books.

Novak, T.P, Hoffman, D.L (1997), “Measuring the flow experience among Web users,” Interval Research Corporation.

Novak, T, Hoffman, D, Young, Y (1998), “Measuring the flow construct in online environments: a structural modeling approach”, Owen Graduate School of Management, Vanderbilt University, working paper.

Novak, T. P., Hoffman, D. L., and Yung, Y. 2000. Measuring the Customer Experience in Online Environments: A Structural Modeling Approach. Marketing Science 19, 1 (Jan. 2000), 22-42

Rettie, R., (2001), An Exploration of Flow during Internet Use, Internet Research, 11(2), 103 – 113.

Simon, H. A. (1971), “Designing Organizations for an Information-Rich World”, in Martin Greenberger, Computers, Communication, and the Public Interest, Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press, ISBN 0-8018-1135-X. pp. 40-41.

Simon, H. A. (1996), The Sciences of the Artificial (3rd ed.), Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-69191-4. pp. 143-144.

van Gorp, Trevor, J. (2006). Emotion, Arousal, Attention and Flow: Chaining Emotional States to Improve Human-Computer Interaction. University of Calgary, Faculty of Environmental Design, Master’s Degree Project.

No comments:

Post a Comment